Untitled, Oaxaca

Oaxaca Contemporary Art Museum (MACO). Oaxaca, Mex.

Curatorship: Carlos Ashida.

Photo credit Francisco Ugarte.

Exhibition text-

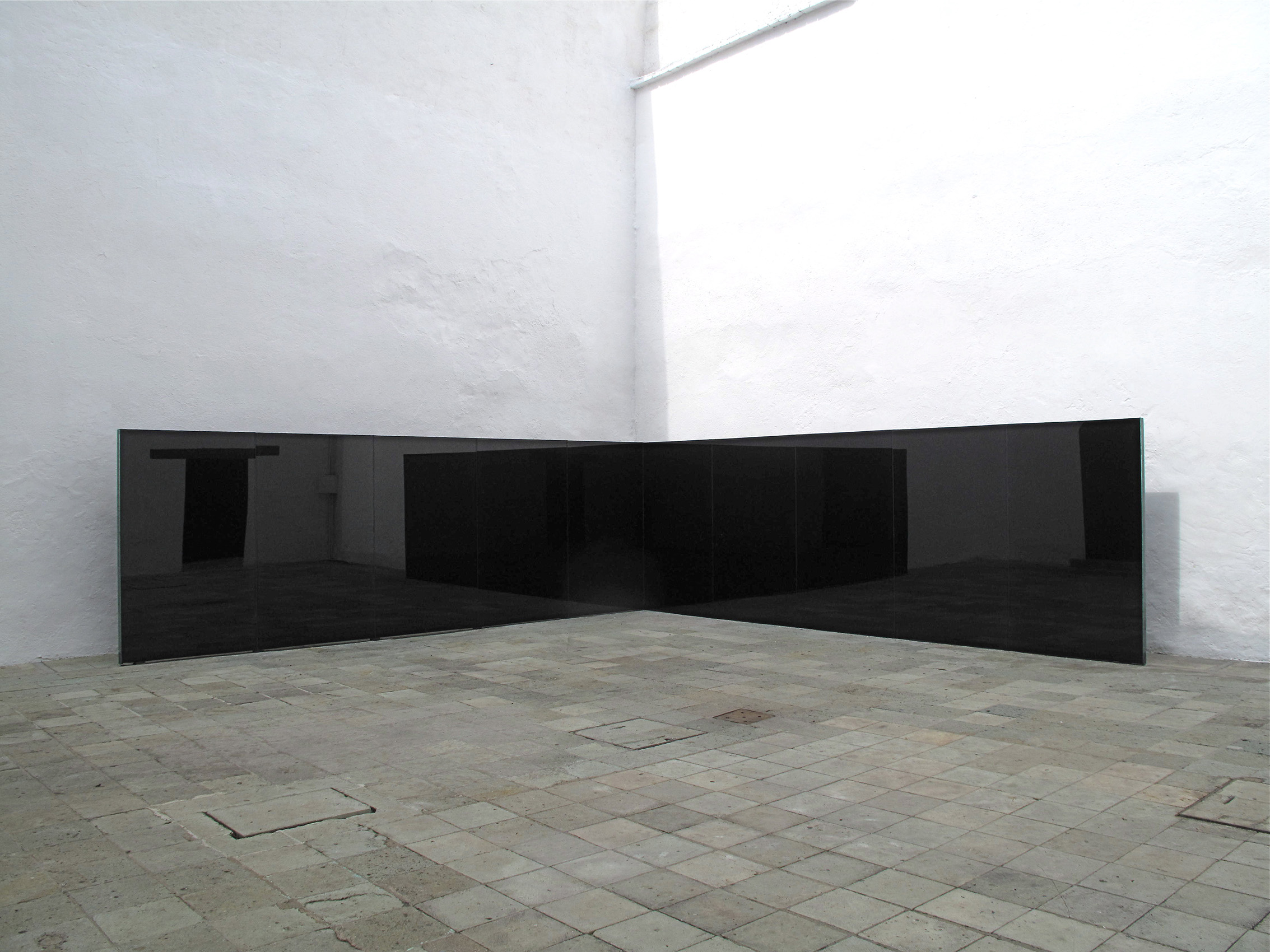

Senda negra / Oaxaca, 2009

Finding a simultaneous and firm support on the fields of art and architecture, Francisco Ugarte (Guadalajara, Jalisco, 1973) developed a solid and sophisticated artistic research with spatial perception as central axis.

Throughout the last ten years, this artist used elements of explicit architectural character to have a bearing on lighting, volume or scale conditions within the contexts in which they are set. These ethereal and austere exogenous components are almost unperceived. They act on the spatial relationships of a site, standing out, distorting or diluting one or several of its traits. This is done in such a way that a well-known space, or a location that the first time visitor expects to be easy to decipher and assimilate due to common sense, displays an unexpected dimension, bestows body to what remained invisible or contradicts the postulates of Euclidian geometry.

In every case, he solves his works with a rational economy of resources, rigorously using the language of abstraction with eagerness for synthesis. Francisco Ugarte acknowledges the intrinsic values of the materials he uses. He resorts on metal for its properties, on glass as it is, and on light due to itself. He uses the qualities of these materials with the certainty of someone who knows there is no possibility for mistakes. The purity and essence of these materials provide a great expressive strength. The categorical affirmation of the own nature of things (as if it would be poetry without metaphors) acquires a metaphysical dimension, in the strict sense of the concept, due to its own intensity.

In his works, Francisco Ugarte disregards any attempt to represent or narrate; he keeps himself within the strict margins of impersonal, cold, and low intensity expression. Nevertheless, his proposals cannot be reduced to a dramatic game. At any rate, the situations of spatial ambiguity created by him push the senses to go beyond themselves; they trespass the ordinary limits of perception and continuously question the nature of things. In this way, Francisco Ugarte’s installations can awake a greater conscience about their bodies and the site where they rove in those spectators that wander about them. The viewers explore their own presence in a precise domain and remain alert about the permanent changes experienced both in the space and (according to the Heracles’ dictum) on themselves, due to the mere time flow.

By displacing the aesthetic end of the object’s materiality to the direct experience of the time and place, Francisco Ugarte causes on the spectator what Yves Bonnefoy denominates “the experience of the site.” This concept is understood as the identification “of a point in space on which our attention centers and becomes withheld,” a site in which the “epiphany of a sign” adds the trait of a more intense reality. It is about a voluntarily chosen site, preferred above the rest of the territory, on which, according to Octavio Paz, “chronologic time suffers a decisive

transformation; it stops flowing, it is no longer a succession and becomes a privileged instant of high temporal current, for the affirmation of a present time and space.” The results obtained under these premises generally constitute extreme situations due to their frugality and evocative capability; they operate that paradoxical mechanism that flow into the dimension that Bachelard denominates as “intimate immensity.”

In his proposal for the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Oaxaca’s (MACO) program denominated Open Cube (Cubo abierto), Francisco Ugarte resorted, as he always does, on his intuition and the first impressions that the place he will intervene cause on him. During his initial visit to the museum’s northern patio, the artist showed more interest on the site’s irregularities rather than on its striking neatness. The dimensions, proportions, wall colors and soberness of this open space, quite literally add-up to characteristic attributes of the museographical white cube, understood as some sort of neutrally aseptic scenario purportedly offering optimal conditions for exhibition. Nevertheless, the orthogonal geometry’s hardness configuring MACO’s northern patio, slightly disturbed by a few windows and doors, finds contradiction on its walls’ texture. The diaphanous Oaxacan atmosphere reveals that this pure and monolithic body shows an abrupt, organic and fragmented surface, brutal on some sections and sensually undulating on others.

It is possible to say that the set of scratches, detachments, scars, patches, protuberances and other accidents that cover every inch of the patio’s four faces represents the chronicle or history of this space, the cartography of a rugged terrain that a uniform layer of luminous white paint, instead of hiding, stands out. The counterpoint found between the imperturbable basic form of the patio and the swarming impure skin that covers it establishes the start mark and the guidelines under which Francisco Ugarte’s intervention develops. It is possible to say that Untitled (Oaxaca 2009,) constitutes a game of contraries materialized in two actions.

The first one consists in painting black all the spaces and all the cavities that face the patio. This simple resource achieves bestowing corporeity to the penetrating light and forcefully establishing polarity between indoors and outdoors. Once in the patio, the contrast between the white walls and the penumbra of the indoor spaces marks a strong rupture, making the massive (more than three feet thick) walls to look like thin, perforated sheets. The second action consists in the installation of a setsquare made with two black-tinted glass walls. Its location, parallel to one of the patio’s corners, generates a narrow (no more than two feet wide) corridor that allows the viewer to follow aroute that once again emphasizes the confrontation between contradictory terms. In this occasion, the reflection effect on the crystal surface, obsessively reproducing its opaque counterpart, adds up to visual and tactile experience of those who travel across the tunnel that has one face (uniform, smooth and cold) made of industrially manufactured crystal and another face (irregular, rough and warm) made out of handcrafted masonry.

The resulting polished, black, “L” shape manifests itself as a paradox. On the one hand, it possesses a solid, blunt and almost totemic presence, while on the other hand, by manifesting itself as a mirror, it vanishes until the point of disappearing. On the interior part, the corridor offers a symmetrical image, while on the external part it cleanly cuts the space as a sharpened obsidian spearhead, annulling the corner in which it is fits and opens illusory perspectives for the view to vanish in multiple directions. It is possible to say that the glass walls act as positive and negative, revealing simultaneously which section of space is real and which virtual. With this series of dichotomous clashes, Francisco Ugarte lays provisional and mobile bridges between the physical and the psychological world, between the material reality and the form in which the perception attempts to grasp it.

Untitled (Oaxaca 2009), inserts itself into a long line of proposals originated in Luis Barragan’s questioning of functionalist modernity, which continues with Mathias Goeritz’s approach to the “emotional architecture,” the experiments of Minimalism, Light and Space Art and specifically for this piece, Bruce Naumann’s self-exploratory exercises. The line finally ends on the nineties, with the author’s generation efforts to continue reconsidering the nature of the artistic work, the frontiers of creativity, and the structures for circulation of cultural assets. In this way, Francisco Ugarte encourages us to saunter, fearlessly scrutinize and uncover some secrets, small prodigies that have been there forever. He achieves this by setting out an intervention that concentrates on the route, on the experience that the spectator can have in the museum, by means of not only the sight but also “at hand level” by palpating the building’s shortcuts and hideouts to understand it as something else, something closer to a laboratory for experiences or a recreational space.

Carlos Ashida.